by Dörte Ilsabé Dennemann

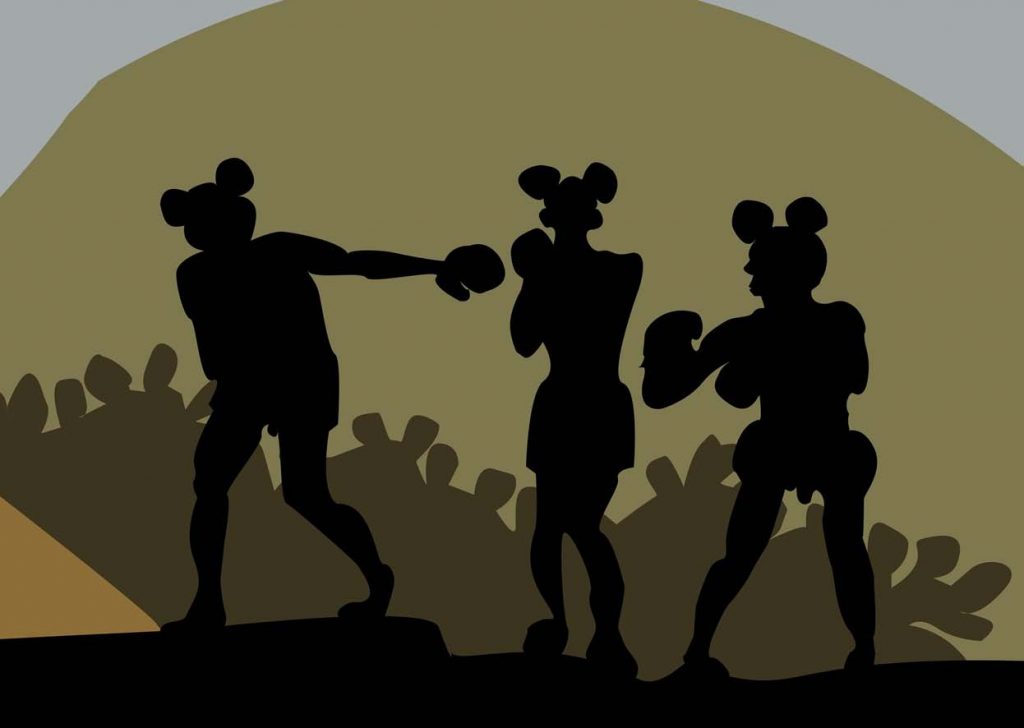

Silhouettes of a high-rise building skyline by night, blue smoke clouds and a small group of people with Mickey Mouse ears, who are playfully swiping at or perhaps actually punching each other? Above the scenery, the light beams of military helicopters are circling coolly and quietly.

In another scene: two watchtowers on the beach, a romantic sunset, in front of which the watchtower guards wave to each other and can only look deeper into each others eyes through binoculars. Between the towers, someone is hauling a lifeless body away. On the horizon, a warship is cruising sedately through the scenery, which is underscored by the staccato of Morse code signals.

In a further scene, night reigns: between the camouflaged bushes and trunks, several black human silhouettes are discernible, pulling on a rope. Perhaps they are in an adventure camp – the jungle rhythms and the mating calls of a tropical frog seem to suggest so. And is it a big stone, a whale or a tank they are pulling?

Under a tree, two reservists seem to have been waiting a long time for their deployment; a sea of emptied bottles has accumulated around them. In another image, an ostrich is sticking its head in the sand as usual; a cripple is struggling away on his crutches; further groups of figures pass by, carrying each other away or hitting each other. Two are already dangling. Are they?

The merry-go-round of these scenes offers excerpts rather than developing any clear narrative or suspense. This strategy also runs through Sharon Paz’s performances, theatrical installations and video works. Indeed, the artist develops her dramaturgies as a collection of isolated combinations of reality and fiction. The mysterious mood of the scenes from ‘IS THIS A GOOD DAY TO START A WAR’ arises from the unaccustomed use and superimposition of documentary references and images with the aesthetic and motif subjects of animated film, which assume a contrasting function.

The scenes refer to social and military events without alluding to any particular incident. Since Sharon Paz is an Israeli artist, it is a natural step to interpret the work within the very specific political situation of her country. Indeed, where else can one watch warships and warplanes from a beach towel and afterwards go to work or to the shopping centr? The everyday, the holiday and the constant political and military (potential) emergency merge into one here and produce a pervasive tension, which often creates its escape valve in the search for entertainment.

The cut-out silhouettes of the sparring figures with Mickey Mouse ears and the military equipment aim at a collective image memory and also refer back in reality to documentary material: photographs from the Palmach archives. The Palmach, founded in 1941 by the Jewish underground organization Hagana in the British Mandate of Palestine, was a paramilitary outfit, which specialized in training.

The Palmach was relatively small but played an important role, since its members were trained in basic military capabilities, which qualified them for positions of command in the subsequent Israeli armed forces. The photographs of the Palmach show young men and women training in attack and defense exercises in quite cheerful camps. These photos were the impulse for Sharon Paz’s work. However, it is not about the reproduction or restating of these photographic documents: Paz is interested in how people manage to accept war as part of normal life.

In the composition of the images, in the choreography of the action and in the sequences of movement, the video resembles a computer game. While the fairy tale ambience à la Lotte Reiniger gives an almost childlike, gaudy, cuteness to the figures, the performance, reinforces the aspect of constant simulation. The endlessly repeated micro movements for example, for which there is no reason and no purpose, are witnesses: these are movements that go nowhere, movement for movement’s sake. Computer game figures complete such movement loops as long as they do not get an action command from the player. Until then, they simulate an activity. Waiting for a command input, the figures seem to be holding themselves in permanent readiness for (violent) action: the perfect reservists, so to say.

Hilarity creeps into the work due to the absurdity of this permanent escalation simulation. However, one cannot be quite sure about the actual aggressiveness of the silhouette figures. There are several known astonishing examples of computer games that are beamed into reality and transform young people into cold-blooded amok runners. It is exactly this situation, i.e. arming oneself against threats as part of being human, that interests Sharon Paz; the idea that rehearsed violence will eventually be useful.

Paz hits the nail on the head with the title: “IS THIS A GOOD DAY TO START A WAR”. The question seems absurd. At least in a Europe, which – according to its own self-conception – waged its last war more than 60 years ago. But in Israel, a country which was tangled up in half a dozen warlike conflicts in the last few decades, and which perceives itself to be encircled by enemies, things are different. Perhaps you really do ask yourself one morning before taking your child to the kindergarten whether someone has not deemed today to start the next war. Thus, military logic creeps into everyday life and, accordingly, you must be prepared for the outbreak of war at any time. Hence every day is a good day to start a war. With the title of her work, Sharon Paz summaries an attitude that is not exclusively Israeli: considering the next war to be completely unavoidable and as a result mentally preparing for it.

Formally-aesthetically striking in “IS THIS A GOOD TIME TO START A WAR”, alongside the use of the pop culture iconography of Mickey Mouse figure, the cut-out silhouettes from early cartoons and the computer game aesthetic, is also the very slide-like ordering of the scenery into panoramas. They allow themselves to be traversed by the eye like a sequence shot in a film, in the foreground and background various small fragments of the action are installed. The panoramas displayed in the exhibition follow a very similar principle and aesthetic. The narrative fragments of the works are in the direction of romantic painting as well as the photo wallpaper of recent design history. Paz succeeds in keeping her worlds of images transparent enough to accommodate images inspired by the Palmach, images from war documentation and fictional film epics, awoken in the observers’ private image bank.